Could mouth breathing be a causal factor in the heart problem that led to Sergio Aguero’s retirement?

Introduction

In October 2021, after only his second start for Barcelona, Sergio Aguero had to be withdrawn early after suffering from chest pains and complaining of dizziness. Recently it has been announced that the 33-year-old will retire from football due to ongoing heart issues related to cardiac arrhythmia. Aguero has arguably had one of the most successful careers in the English premier league. However, it is not without a shadow casting over his footballing skills when retiring from heart health issues at such a young age. Could this have been prevented, or better yet, could his risk of further complications be significantly reduced by looking at his breathing? When looking at pictures of Aguero (figure 1.), there is something consistent, which perhaps to the untrained eye is nothing of significance. However, those who are up to date with their breathing research will spot it from a mile off. Sergio Aguero is a serial mouth breather. Ok, so what? Doesn’t everyone breathe through the mouth?

Yes, many do, but if you’ve read The Oxygen Advantage by Patrick McKeown and are up to date with the latest science. You will notice that the evidences suggests that breathing through the mouth can cause an array of health issues, and it is not ideal for exercise performance. This article will discuss a potential hypothesis as to why Sergio Aguero and perhaps many other athletes have ultimately led to his career-ending health problems related to the heart: mouth breathing.

Before we go on, this is not a medical diagnosis. There is no prior medical history other than the little published on the internet. This writing is simply a hypothesis based on knowledge of the cardiopulmonary system, specifically the relationship between sleep, breathing, and the heart. That said, I am a fully qualified respiratory and sleep scientist who spent the latter part of a decade as a clinician running lung function labs, specialising in exercise physiology and sleep-related breathing disorders. Now consulting online with people regarding their breathing and sleep, helping improve stress, anxiety and exercise performance.

This blog will be rather heavy on the science to supply enough evidence to build a case to examine why mouth breathing can lead to cardiac issues in athletes who may have dysfunctional breathing patterns despite otherwise being fit and healthy. First, we will look at breathing during rest and exercise, how it impacts the autonomic nervous system, and then delve a little deeper into some of the elements of pathophysiology related to breathing and cardiac health.

Figure 1. a small collection of Sergio Aguero playing soccer at different periods of his life from google images (2021).

Breathing physiology

In healthy individuals, at rest and during lower-intensity exercise, nasal breathing is usually efficient to supply enough oxygen to the demand of the energy requirements of the activity. However, as exercise increases, there is further demand to supply oxygen to the working muscles. Through various detection methods known as receptors, the brain receives signals to increase cardiac output. Thus, by a further contribution of the sympathetic nervous system heart rate increase, the ventricles in the heart pump blood more forcefully, which delivers further blood flow to the workings muscles supplying them with oxygen to produce ATP aerobically. However, this also requires an increased demand for oxygen to the cardiac cells known as myocytes. At a given point during the exercise, usually, anywhere between 30-60% of VO2 max (even higher for endurance athletes), the metabolic demand for energy is higher than the supply of oxygen. As a result, energy production occurs through a different medium called anaerobic glycolysis.

At this point, there is a considerable production of CO2, the primary driver of ventilation, and due to a feeling of air hunger, most people will begin to breathe through their mouths. Contrarily, if a person breathes through their mouth at rest, it could be congestion, a deviated septum or simply a poorly learnt breathing pattern during childhood. In this case, people may become habitual mouth breathers. Unfortunately, adopting this breathing pattern at rest, during low-intensity exercise, and even when potentially sleeping could be hurting their cardiac and metabolic health, contributing to career-ending health conditions.

Suppose we break down the above paragraph for a moment and look at what is going on with breathing. In that case, we can make a relatively straightforward statement related to stress and physiology. There is a point within exercise where the mouth opens when the metabolic stress of exercise is excessive. Thus, mouth breathing signals that the body is under excessive stress. Therefore, habitual mouth breathers are more likely to have increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system than the parasympathetic nervous system. Sympathetic overactivity and vagal impairment are powerful negative prognostic indicators for morbidity and mortality associated with arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death [1]. That already gives us something to consider with athletes who continually put their mind and body under stress, especially when contemplating breathing pattern disorders and a history of cardiac issues. Here we are just touching the surface as a basis of exercise physiology but let us take a deeper dive into the significance of habitual mouth breathing.

Detecting Mouth Breathing Early

Many studies have described the consequences of mouth breathing in adults and children [2,3,4] such that in 2015, Pacheco et al. decided it would be worthwhile to put some guidelines together for clinical recognition of mouth breathing in children [5] so that it can be corrected early. The most significant correlate with prognosis is a lack of sealed lips through visual assessment. Parents and health professionals should be observing young children to document whether their mouth is wide open at rest and during sleep. Another thing to note is their tongue position; in mouth breathers, the tongue can take a low and forward position, which is common in the presence of hypertrophic palatine tonsils as an attempt to increase posterior airway space and ease breathing [6]. Poor tongue posture at night can lead to obstructive sleep apnoea [7]. (check out my podcast with Myofunctional Therapist Jen) With this assumption, if a child is a habitual mouth breather, they are highly likely to have a breathing pattern disorder as an adult, more specifically related to sleep-disordered breathing, which we will discuss later.

Mouth Breathing and the Heart

Mouth breathing not only causes dental issues in children but is also associated with an array of health and behaviour issues [8]. Although mouth breathing gets air into the lungs, it bypasses many of the beneficial effects of nasal breathing. For example, the nose plays an essential role in respiration as it warms, humidifies, and cleanses/filters air to prepare it for delivery to the lung [9]. When comparing ventilation, those who breathe through the mouth typically hyperventilate compared to those who breathe through the nose, leading to a reduction in arterial carbon dioxide (CO2), especially when it comes to exercise [10]. CO2, traditionally thought of as a waste product, is necessary for many physiological processes related to oxygen delivery to working muscles, i.e., the heart. Recent research suggests that CO2 plays a vital role in physiological signalling in breathing and oxygen delivery by a mechanism involving protein Connexin 26 [11]. This specific connexin binds with CO2 and regulates breathing in the medulla oblongata. Connexins are a family of membrane-spanning proteins named according to their molecular weight. They form membrane channels mediating cell-cell communication, which play an essential role in propagating electrical activity in the heart [12]. With mouth breathers typically over-breathing during exercise and at rest, this hyperventilation could reduce the presence of CO2 to bind with connexin, altering levels of this communication protein that over time leads to perturbations in the electrical activity of the heart cells and cardiac arrhythmia.

While this is only speculative, it is not the first hypothesis to suggest issues with mouth breathing and athletes’ cardiac-related health issues. For example, in a recent conversation with Dr George Dallam, a Professor in the Department of Exercise Science, at Colorado State University-Pueblo, he stated a case for Nitric oxide or lack of during mouth breathing being an issue that may cause cardiac scarring in endurance athletes [13].

In this discussion, he states:

“I have a working hypothesis that the relatively more remarkable hyperventilation seen during oral breathing in exercise might be a contributing factor in reduced coronary blood flow – via both a lesser release of nitric oxide (assuming it gets that far downstream from the lung) and generally lower blood CO2 resulting in less vasodilation (maybe even some vasoconstriction) in the coronary arteries. Of course, at rest, significant hyperventilation, as during a panic attack, is associated with occasional coronary spasms and fatal MI in some susceptible individuals. During exercise, similar hyperventilation produced by breathing orally might be the basis for the increased myocardial scarring seen in long term endurance athletes (literally all of whom breathe orally when training/racing).”

There are a few interesting points in his hypothesis, such as reducing vasodilation due to low blood CO2. Reduced arterial CO2 affects cardiac functioning in two ways that are relatable to this overall hypothesis. Firstly, it reduces blood flow to the heart. [14,15] Secondly, the bond between red blood cells and oxygen is strengthened, leading to reduced delivery of oxygen to the heart muscle (Read; Haldane vs Bohr Effect) [16]. An experimental study on nine human subjects showed that voluntary over-breathing reduced arterial partial pressure of CO2 from normal levels of 40 mmHg to 20 mmHg, increased coronary blood vessel resistance by 17% and decreased coronary blood flow by 30%. [16]. Hyperventilation leads to respiratory alkalosis, increasing coronary vasoconstriction and the risk of cardiac arrhythmia. [17] Finally, In patients with central sleep apnoea, there is a 20 times greater risk of cardiac arrhythmia for hypercapnic patients than eucapnic suggesting the ventilatory instability and potentially central chemosensitivity to CO2 plays a role in cardiac arrhythmias.[18] Therefore, altogether the evidence suggests that low CO2 could lead to cardiac arrhythmia and, in this case, supports our hypothesis that unnecessary mouth breathing might play a role in developing heart conditions in athletes.

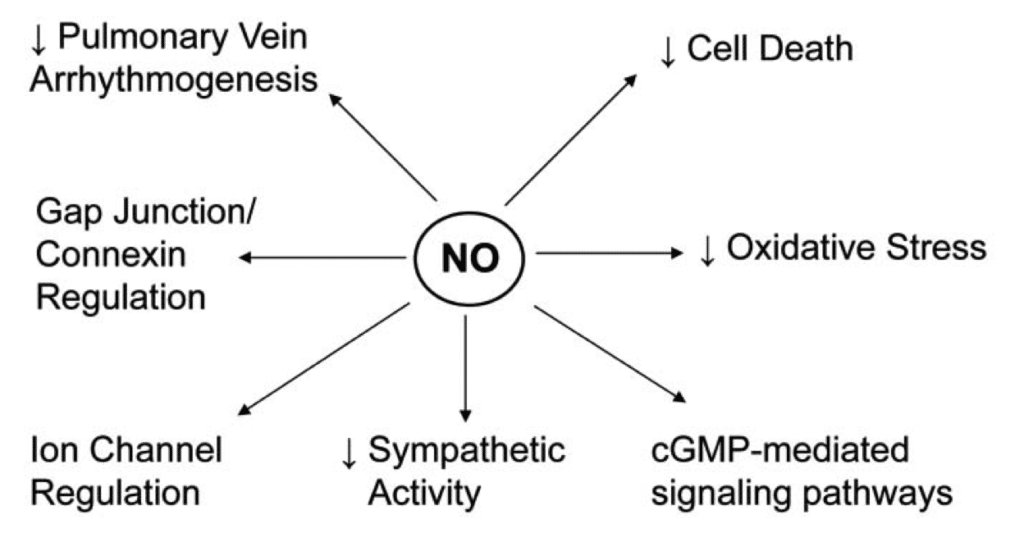

The other thing to discuss is the role of nitric oxide (NO) in this whole situation. NO prolongs ventricular repolarisation in large animals under certain circumstances, such as during sympathetic stimulation or high-pressure intracoronary perfusion as during exercise. NO deficiency seems to mediate cardiac glycoside-induced ventricular arrhythmias in intact and isolated ventricular preparations. Data from large animal experiments have shown that NO reduces the severity and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias induced by sympathetic stimulation or acute ischemia.[19] Suppose this is the case, during exercise or under stress conditions (mouth breathing), then, in that case, NO plays a significant role in the electrical pathway of the heart muscles, as without vascular repolarisation, there is no available electrical conductance for muscular contraction. Furthermore, there is also evidence that basal NO production protects against arrhythmia. Elevation in plasma levels of the endogenous NOS inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) is associated with adverse cardiovascular events following cardiac and non-cardiac surgeries and in patients with peripheral artery disease [20]. There are seven proposed mechanisms to how NO protects against cardiac arrhythmia (see figure 2) [20]. Interestingly, NO has a downregulation on sympathetic nervous system activity and plays a role in the gap junction connexin regulation, as previously discussed as potential issues related to how mouth breathing can increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmia. NO is produced by all cells in the heart, and therefore local production may be substantial even if nasal production of NO does not reach the cardiac cells.

Nonetheless, NO produced in the paranasal sinuses contributes to the distribution of pulmonary blood flow and supports efficient ventilation/perfusion matching within the lungs, increasing oxygen uptake by 17% compared to mouth breathing [21], where NO production is significantly reduced and leads to increase pulmonary vascular resistance when compared to nasal breathing [22]. Pulmonary vascular resistance is lowest at FRC, where intrathoracic pressure is neutral. At low lung volumes, it increases due to the compression of larger vessels. As seen in mouth breathing, high lung volumes increase PVR due to the compression of small vessels, not ideal for cardiac vasculature. These data suggest that NO plays a significant role in gas exchange in the lungs. Studies show that NO carried by Hb dilates the microvasculature to increase local blood flow and thus oxygen delivery to working muscles, i.e., the heart. [21] Although free NO cannot exist in meaningful amounts in the blood, as it is rapidly eliminated by reactions with oxygenated Hb [23], NO bioactivity is preserved in RBCs in the form of S-nitrosohemoglobin (SNO-Hb). SNO-Hb is especially well suited to regulate local blood flow because the release of SNO from Hb is linked thermodynamically to the release of oxygen [24, 25]. A pilot study of 15 healthy volunteers showed that inhaled NO increases blood concentrations of SNO-Hb [26]. Therefore, giving evidence to suggest that if chronic mouth breathing, particularly during high-intensity work, could lead to a reduction in oxygen diffusion at the levels of the lungs and oxygen delivery to the heart via a reduction in SNO-Hb, which may also contribute to issues related to the electrophysiology of the heart. Add that to the already mentioned ventilatory instability and perturbations from low CO2; growing evidence suggests that athletes with breathing dysfunctions or chronic mouth breathing may have issues related to all three gases in the respiratory cycle contributing to the overall stress on the cardiopulmonary system.

Figure 2. Seven proposed mechanisms to how nitric oxide plays a role in protective of cardiac arrhythmia [20].

Biomechanical issues related to mouth breathing

Let us now move away from the biochemical issues related to the cardiorespiratory system and focus on the mechanical issues. Mouth breathing affects the biomechanics of upper airway muscles [27] and diaphragm action [28]. It adversely affects upper airway collapse in sleep apnea [29]. Sleep apnea may contribute to arrhythmias due to acute mechanisms, such as generation of negative intrathoracic pressure during futile efforts to breath, intermittent hypoxia, and surges in sympathetic activity. In addition, OSA may lead to heart remodelling and increase arrhythmia susceptibility [30]. Therefore, these data contribute evidence to suggest that athletes with dysfunctional breathing are at considerable risk of OSA and should be screened as a part of their medical workup.

Furthermore, elevated respiratory drive, such as during high-intensity exercise, when persistent, tends to produce chronic hypertonicity of respiratory muscles, and this can contribute to abnormal breathing patterns [31]. Mouth breathing, often observed into the upper chest (thoracic) and asynchronous breathing resulting from increased respiratory drive [32]. Persistent increases in inspiratory muscle tone, not balanced by relaxation of these muscles, can overload respiratory muscles and contribute to fatigue [33]. Under exercise-induced respiratory muscle fatigue, blood is redirected from the working muscles to the respiratory muscles by a concept known as the respiratory metaboreflex, inducing fatigue and reducing exercise tolerance [34]. It is unknown whether this reflex induces cardiac blood flow redistribution.

Interestingly, this could further contribute to cardiac problems related to endurance athletes, especially those with chronic mouth breathing. In contrast, nasally adapted recreational athletes show increased ventilatory efficiency as demonstrated by a reduction in minute ventilation compared to mouth breathing during a graded exercise test [9], which speculates that nasal breathing may delay or attenuate the effects of respiratory muscle fatigue on the metaboreflex.

Does Sergio Aguero Have A Breathing Pattern Dysfunction?

Given the information in this article, we can hypothesise that mouth breathing or patterns of breathing dysfunction may lead to heart problems in some athletes. Over the years, there have numerous cases of soccer players collapsing on the pitch or in training. For example, Marc-Vivien Foé was part of Cameroon’s squad for the 2003 FIFA Confederations Cup and passed away on the pitch. Iker Casillas (2019), the Spanish national team legend, suffered a heart attack during training. Just last year, Christian Eriksen’s heartbeat briefly stopped after collapsing in the opening match of Group B Euro 2020. Could these all be cases of heart-related breathing issues?

What about Aguero?

Figure 3. Sergio Aguero as a young child clearly showing relaxed mouth breathing – taken from fan page.

There is only one photo as a young child (figure 3). On visual inspection of the still, his mouth is open and his tongue in a down and forward. As an adult, there are thousands of examples type, Sergio Aguero, on Google images to see how often he is breathing through his mouth or has his mouth open at rest. For example, look at this short training clip where he is undergoing some recent training at Barcelona at 2min 55sec. He is training at lower intensities with his mouth wide open. In January 2021, on his twitter profile he announced that he tested positive for COVID with symptoms. However, it is not known how severe his symptoms were or whether this impacted his breathing function and his cardiologist has doubted that. This article is merely an observation of a consistent theme in image. That on investigation after being stretchers off the pitch back in October, spurred some thoughts. I thought if somehow I could contribute through a short run through the literature, it could help raise awareness of the matter and seek change in the medical examination of athletes.

Conclusion

Professional athletes spend years adapting to exercise stress to ensure peak physical fitness. However, it is not common knowledge to investigate or maximise breathing efficiency. Whether athletes regularly undergo breathing assessments for dysfunctional breathing patterns or coaches assess how their players breathe during training and competition is unknown. It is doubtful that it is regularly investigated because it is such a niche area of science and does not lay in the specific interest to exercise physiologists. However, it would seem appropriate given that breathing directly impacts physiological and metabolic changes during exercise. This scientific blog has discussed the various mechanisms to which mouth breathing in athletes could lead to issues with cardiac arrhythmia or ischemia, both coming from the biochemical view of the three respiratory gases oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitric oxide – as well as the biomechanical issues concerning the respiratory muscle fatigue and sleep-disordered breathing.

Sergio Aguero will be seeing some of the best cardiac experts that Spain has to offer; however, much of these data presented are at the forefront of scientific papers and research in the area is sparse. Therefore may not be common knowledge to those who attend medical school where the evidence takes more than 10 – 15 years to reach practical guidelines. Nevertheless, there is enough evidence to warrant assessment by a specialist in breathing patterns disorders, sleep-disordered breathing, and a cardiac assessment in a multidisciplinary manner. This is because the human body works in a manner where all physiology is interconnected. Therefore, we need to be investigating the body as an integrative system, especially in complex situations such as those related to arrhythmia of unknown cause.

Acknowledgements

I would like to say thank you to Nick Heath AKA The Breathing Diabetic for proofreading and helping with suggestions in editing of this article. Nick is making a fantastic contribution to raising awarenss around the importance of breathing and diabetes, I recommend you check him out. Also for the continual work that Patrick McKeown, James Nestor and the team at Shift Adapt & The HHP Foundation do to promote interest in the benefits of correct breathing.

References

- Herring, N., Kalla, M. & Paterson, D.J. (2019) The autonomic nervous system and cardiac arrhythmias: current concepts and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Cardiol16, 707–726 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-019-0221-2

- Junqueira P, Marchesan IQ, de Oliveira LR, Ciccone E, Haddad L, Rizzo MC.(2010) Speech-language pathology findings in patients with mouth breathing: multidisciplinar diagnosis according to etiology. Int J Orofacial Myology. ;36:27-32.

- Cunha DA, Silva GAP, Motta MEFA, Lima CR, Silva HJ. (2007) Mouth breathing in children and its repercussions in the nutritional state. Rev CEFAC. ;9(1):47-54.

- Okuro RT, Morcillo AM, Sakano E, Schivinski CIS, Ribeiro MAG, Ribeiro JD. (2011) Exercise capacity, respiratory mechanics and posture in mouth breathers. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. ;77(5):656-62.

- Pacheco, M. C. T., Casagrande, C. F., Teixeira, L. P., Finck, N. S., & Araújo, M. T. M. D. (2015). Guidelines proposal for clinical recognition of mouth breathing children. Dental press journal of orthodontics, 20, 39-44.

- Friedman, M., Hamilton, C., Samuelson, C. G., Lundgren, M. E., & Pott, T. (2013). Diagnostic value of the Friedman tongue position and Mallampati classification for obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 148(4), 540-547.

- Jefferson, Y. (2010). Mouth breathing: adverse effects on facial growth, health, academics, and behavior. Gen Dent, 58(1), 18-25.

- Allen, R. (2017). The health benefits of nose breathing. Nurses Clinical Review. Nursing in general practice.

- Dallam, G. M., McClaran, S. R., Cox, D. G., & Foust, C. P. (2018). Effect of nasal versus oral breathing on Vo2max and physiological economy in recreational runners following an extended period spent using nasally restricted breathing. International Journal of Kinesiology and Sports Science, 6(2), 22-29.

- Van de Wiel, Joseph, Meigh, Louise, Bhandare, Amol M., Cook, Jonathan P., Nijjar, Sarbjit, Huckstepp, Robert T. R., Dale, Nicholas, 2020. Connexin26 mediates CO2-dependent regulation of breathing via glial cells of the medulla oblongata. Communications Biology, 3 (1).

- Moscato, S., Cabiati, M., Bianchi, F., Vaglini, F., Morales, M. A., Burchielli, S., … & Mattii, L. (2018). Connexin 26 expression in mammalian cardiomyocytes. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-11.

- Dallam & McPhilimey. (2021). https://performancethroughhealth.com/oral-vs-mouth-breathing-with-george-dallam/.

- Kazmaier, S. Weyland, A. Buhre, W. et al. 1998 Effects of respiratory alkalosis and acidosis on myocardial blood flow and metabolism in patients with coronary artery disease. Anesthesiology 88:831-7.

- Neill, W.A. Hattenhauer, M. 1975 Impairment of myocardial O2 supply due to hyperventilation. Circulation. Nov; 52 (5):854-8.

- Rowe GG, Castillo CA, and Crumpton CW. 1962. Effects of hyperventilation on systemic and coronary hemodynamics. American Heart Journal, January 1962 Vol 63: 67–77.

- King, J.C. Rosen, S.D. and Nixon, P.G. 1990 Failure of perception of hypocapnia: physiological and clinical implications. Journal Royal Society Medicine. Dec;83(12): 765–767

- Javaheri, S., & Corbett, W. S. (1998). Association of low PaCO 2 with central sleep apnea and ventricular arrhythmias in ambulatory patients with stable heart failure. Annals of internal medicine, 128(3), 204-207.

- Wang, L. (2001). Role of nitric oxide in regulating cardiac electrophysiology. Experimental & Clinical Cardiology, 6(3), 167

- E Burger, D., & Feng, Q. (2011). Protective role of nitric oxide against cardiac arrhythmia-an update. The Open Nitric Oxide Journal, 3(1).

- Premont, R. T., Reynolds, J. D., Zhang, R., & Stamler, J. S. (2020). Role of nitric oxide carried by hemoglobin in cardiovascular physiology: developments on a three-gas respiratory cycle. Circulation research, 126(1), 129-158.

- Lundberg, J. N., Lundberg, J. M., Settergren, G., Alving, K., & Weitzberg, E. (1995). Nitric oxide, produced in the upper airways, may act in an’aerocrine’fashion to enhance pulmonary oxygen uptake in humans. Acta physiologica scandinavica, 155(4), 467-468.

- Lundberg, J. O. N., Settergren, G., Angdin, M., Astudillo, R., Gelinder, S., Liska, J., & Weitzberg, E. (1998). Lower pulmonary vascular resistance during nasal breathing: modulation by endogenous nitric oxide from the paranasal sinuses. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 157, A230.

- Gibson, Q. H., & Roughton, F. J. W. (1957). The kinetics and equilibria of the reactions of nitric oxide with sheep haemoglobin. The Journal of physiology, 136(3), 507-526.

- Singel, D. J., & Stamler, J. S. (2005). Chemical physiology of blood flow regulation by red blood cells: the role of nitric oxide and S-nitrosohemoglobin. Annu. Rev. Physiol., 67, 99-145.

- Zhang, R., Hess, D. T., Qian, Z., Hausladen, A., Fonseca, F., Chaube, R., … & Stamler, J. S. (2015). Hemoglobin βCys93 is essential for cardiovascular function and integrated response to hypoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(20), 6425-6430.

- Tonelli, A. R., Aulak, K. S., Ahmed, M. K., Hausladen, A., Abuhalimeh, B., Casa, C. J., … & Dweik, R. A. (2019). A pilot study on the kinetics of metabolites and microvascular cutaneous effects of nitric oxide inhalation in healthy volunteers. PloS one, 14(8), e0221777.

- Lee S H , Choi J H, Shin C, Lee H M, Kwon S Y, Lee S H. (2007). “How does open- mouth breathing influence upper airway anatomy.” Laryngoscope 117(6): 1102- 1106.

- Yi L C , Jardim J R , Inoue D P, Pignatari S S. (2008). “The relationship between excursions of the diaphragm and curvatures of the spinal column in mouth breathing children.” J Pediatr (Rio J) 84(2): 171-177.

- Kim E , Choi J , Kim K W, Kim T H ,Lee S H ,Lee H M, Shin C, Lee K Y ,Lee S H, (2010). “The impacts of open-mouth breathing on upper airway space in obstructive sleep apnea: 3-D MDCT analysis.” Eur Arch Otorhinology DOI: 10.1007/s00405-010- 1397.

- Geovanini, G. R., & Lorenzi-Filho, G. (2018). Cardiac rhythm disorders in obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of thoracic disease, 10(Suppl 34), S4221.

- Romagnoli I, Gorini M, Gigliotti F, Bianchi R, Lanini B, Grazzini M, Stendardi L, Scano G. (2006) Chest wall kinematics, respiratory muscle action and dyspnoea during arm vs. leg exercise in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf). Sep;188(1):63-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01607.x. PMID: 16911254.

- Verschakelen J A and Demedts M G (1995). “Normal thoracoabdominal motions:influence of sex, age, posture, and breath size.” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 399-405.

- Janssens, L., Brumagne, S., McConnell, A. K., Raymaekers, J., Goossens, N., Gayan-Ramirez, G., … & Troosters, T. (2013). The assessment of inspiratory muscle fatigue in healthy individuals: a systematic review. Respiratory medicine, 107(3), 331-346.

- Romer, L. M., & Polkey, M. I. (2008). Exercise-induced respiratory muscle fatigue: implications for performance. Journal of Applied Physiology, 104(3), 879-888.

Comments

Such an odd article using photos of a footballer with his mouth open as an argument in this case. Elite level footballers don’t just run around silent on a pitch. They’re vocal, shouting to their teammates, opposition and referees.

It isn’t a steady state exercise and players are constantly bursting with pace, acceleration, speeding up and slowing down. Therefore, the likelihood to have facial reactions when they’re just about to sprint, turn or receive a pass or even about to get tackled. Footballers are always going to be making facial expressions therefore leading to a millisecond photograph showing them with their mouth open.

It’s also shown that low affect facial expression shows improvement in performance in long distance runners. Do we expect footballers now to run about breathing out of their nose and showing little to zero facial expression.

In terms of sleeping, Google “Sergio Aguero Sleeping”. You will see a selfie by Messi showing Aguero sleeping with his mouth closed.

In no way am I discrediting the research highlighted in this article however there are limitations when applying to different sports. The biomechanics and demand put upon the body in the likes of marathon runners, weightlifters will allow for more control over breathing in comparison to footballers and other sports where there’s far less scope to control mouth/nose breathing.

Thanks for your comment Eoghan,

If you google image search Sergio Aguero is open mouth almost all the time. I am aware this is very speculative in his case but the overall intention of the article was to highlight the possibility of dysfunctional breathing being a problem for athletes. Of course, there are limitations, and talking during a game is necessary, but what about during recovery, when not in action, at home, when sleeping, and for all the other time. That’s time for the nose to be used for sure.

Appreciate you reading the article and commenting.

Martin